The Alchemy of Absence: Reclaiming Narrative Through Ruin and Reconstruction

There's a profound beauty in imperfection. We chase it in our lives, strive for it in art, and often overlook it in the objects that surround us. Consider the antique accordion, gathering dust in a forgotten corner of a music shop. Its bellows might be cracked, keys missing, its once-bright finish dulled with age. Many would see only a broken instrument, destined for the scrap heap. But I see a story. A history etched into every scar, a silent symphony of resilience.

My grandfather played the accordion. Not professionally, but with a joyful abandon that filled our family gatherings. He's gone now, but the memory of his music – often punctuated by the occasional discordant note – remains a palpable warmth. I inherited his old accordion, a battered Hohner Monarch, a testament to years of use and a few unfortunate mishaps. It's more than just an instrument; it's a vessel of memory, a tangible link to a cherished past.

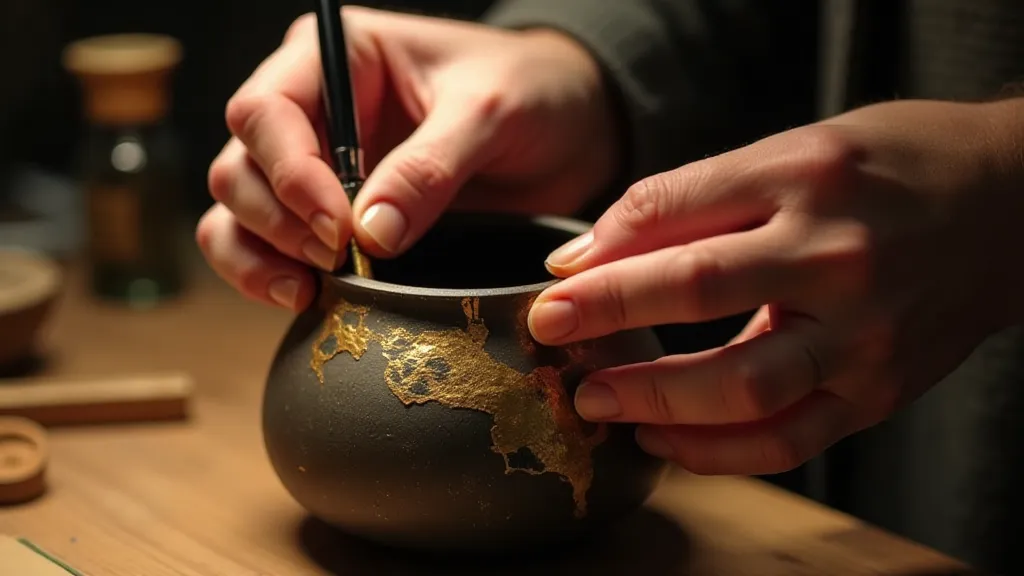

And it's broken. Badly. A key sticks, the bellows leak, and the overall state suggests a life lived hard. Fixing it perfectly isn't the goal. The idea of replacing those imperfections with pristine uniformity feels… disrespectful. This leads me to the philosophy of Kintsugi, the ancient Japanese art of repairing broken pottery with gold, silver, or platinum.

The Philosophy of Kintsugi: Embracing Flaws

Kintsugi (金継ぎ), literally "golden joinery," isn’t about erasing damage; it’s about highlighting it. It embodies the Japanese aesthetic philosophy of *wabi-sabi*, which finds beauty in transience and imperfection. Instead of disguising the cracks and chips, Kintsugi artisans meticulously repair them with precious metals, transforming the damage into a feature, a testament to the object’s journey. The resulting piece isn't diminished by its history; it’s *enhanced* by it. The repairs become integral to its beauty, adding layers of meaning and character.

Imagine a favorite teacup, dropped and shattered. Most would discard it without a second thought. But in the hands of a Kintsugi artisan, those fragments are carefully gathered, meticulously rejoined, and the cracks are filled with glittering gold. The repaired teacup isn’t just functional; it's a work of art. It carries the story of its fall, its fragility, and the skilled hands that brought it back together. The gold isn’t a concealment; it's a celebration of survival, a visual declaration of resilience.

Applying Kintsugi to Narrative: Finding Gold in Discarded Dreams

The principles of Kintsugi extend far beyond the realm of pottery. I find them remarkably insightful when considering the creative process – particularly writing. How many of us have abandoned drafts, discarded ideas, and shelved projects, convinced they were failures? How often do we berate ourselves for those moments of creative block or those chapters that simply *didn’t work*?

What if we approached those discarded fragments with the same reverence a Kintsugi artisan brings to a broken bowl? What if, instead of seeing those failures as dead ends, we recognized them as valuable pieces of our narrative journey?

Consider a scene that felt forced, a character that felt flat, a plot twist that fell completely flat. Instead of deleting it entirely, try reframing it. Could that ‘failed’ scene be reworked as a subtle foreshadowing? Could that underdeveloped character become a poignant supporting role? Could that disastrous plot twist be repurposed as a moment of unexpected humor or a catalyst for character growth?

My own writing has benefited immensely from this approach. I once had a short story I deemed a complete failure – overly sentimental, poorly paced, and riddled with clichés. I shelved it, convinced it was beyond redemption. Years later, I reread it, not with the critical eye of a writer, but with the curiosity of an observer. I realized that while the story itself wasn’t salvageable, the *exercise* of writing it had unearthed valuable insights into character development and narrative structure. Those insights informed my subsequent work, making it stronger and more authentic.

The Craftsmanship of Imperfection: A Restorer’s Perspective

The process of Kintsugi, like any form of restoration, requires patience, skill, and a deep respect for the object being repaired. It's not about quick fixes or cosmetic repairs; it’s about understanding the object’s history and honoring its integrity. It’s a reminder that true beauty often lies in the imperfections, in the marks left by time and experience.

Similarly, in writing, the ‘restoration’ of a discarded idea often requires a willingness to step back, to re-examine our assumptions, and to experiment with different approaches. It might involve cutting passages we thought were essential, rearranging scenes, or even completely reimagining the story’s premise.

Collecting antique instruments like my grandfather's accordion offers a related lesson. It's tempting to seek out pristine examples, those untouched by time or damage. But there's a unique charm in owning an instrument that bears the marks of its past – a faded finish, a replaced key, a slight crack in the wood. These imperfections tell a story, connecting us to the instrument’s history and the people who played it before us.

Transforming Absence into Presence

The philosophy of Kintsugi teaches us that absence isn’t necessarily a void. It can be a catalyst for creation, a source of strength and beauty. The cracks in a broken object become not weaknesses, but features, adding layers of meaning and character. The discarded draft becomes a wellspring of inspiration. The painful memory becomes a source of empathy and understanding.

Let us embrace the imperfections, the failures, the absences in our lives and in our creative endeavors. Let us find the gold within the broken pieces and transform them into something new, something beautiful, something uniquely our own. The alchemy of absence lies in our ability to see the potential for creation within the ruins of what once was – a lesson I learned from a cracked accordion and a profound Japanese art form.