The Gilded Thread: Finding Harmony Between Flaws and Form in Storytelling

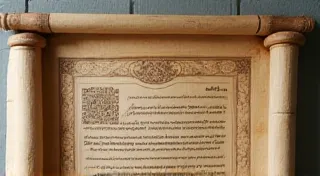

There’s a peculiar comfort found in observing things that have been broken and meticulously, lovingly, repaired. Not concealed, mind you, but *revealed*. Think of a treasured antique accordion, its bellows cracked, its keys chipped, yet still breathing out melancholic tunes. It’s a history etched into its very being – a tangible record of laughter, tears, and the relentless passage of time. And it’s in that visible repair, that visible mending, that a profound beauty resides. This is the essence of *Kintsugi*, the Japanese art of repairing broken pottery with gold, and a potent metaphor for the art of storytelling itself.

The Philosophy of Imperfection

Kintsugi isn't about erasing damage. It's about celebrating it. The golden lacquer doesn't attempt to hide the cracks; instead, it draws attention to them, transforming flaws into focal points of exquisite detail. The philosophy underpinning it aligns perfectly with the Wabi-Sabi aesthetic – an appreciation for the beauty of imperfection, impermanence, and the natural progression of life. Western cultures often equate beauty with perfection – flawless skin, symmetrical features, error-free prose. But Kintsugi, and the principles it embodies, challenge this notion, suggesting that true beauty often lies in the acceptance and elevation of what is broken.

My Accordion and the Echoes of Time

I own an old Hohner accordion, a relic from my grandfather's travels in Europe. It doesn't play perfectly. Several keys stick, a few are missing, and the leather bellows leak a little air. I remember sitting on his knee as a child, mesmerized by the swirling, joyful melodies he coaxed from it. He’s gone now, but the accordion remains, a constant, tactile link to my past. For years, I considered having it professionally restored, erasing the signs of its age and use. The temptation was strong – to return it to a state of pristine functionality, a pristine appearance.

But something always held me back. The cracks and imperfections weren't just marks of decay; they were testament to a life lived, a story played out. They whispered of bustling marketplaces in Vienna, of smoky cafes in Paris, of countless evenings filled with laughter and music. To erase those imperfections would be to erase a part of my grandfather, a part of my family history. Now, when I play it, the slightly off-kilter notes are a reminder of him, a gentle echo of his presence.

The Writer's Kintsugi: Embracing Vulnerability

This concept applies powerfully to the craft of writing. We are often taught to strive for polished prose, for grammatical perfection, for plot structures that are airtight and predictable. The relentless pursuit of this "perfect" narrative can lead to writing that feels sterile, generic, and ultimately, lacking in soul. Think of those novels you’ve put down halfway through, feeling emotionally detached and hollow – those are often the products of this relentless pursuit of flawlessness.

The writer’s Kintsugi is embracing the cracks, the vulnerabilities, the unresolved questions that naturally arise in the creative process. It’s allowing the rough edges to remain visible, even if they’re uncomfortable. It’s acknowledging that not every question has an answer, and sometimes, the most compelling narratives are those that leave room for ambiguity and interpretation.

Consider a memoir grappling with a difficult family relationship. It could be tempting to sanitize the narrative, to portray everything in a flattering light. But true resonance comes from honestly confronting the complexities, the contradictions, the uncomfortable truths. The “golden lacquer” in this case isn’t about hiding the pain; it's about illuminating it with insight, compassion, and a willingness to be vulnerable.

Similarly, in fiction, a narrative doesn’t need to neatly tie up every loose end. Sometimes, the most powerful moments are those that linger in the reader’s mind long after the final page is turned – moments that spark curiosity, provoke introspection, and leave a lasting emotional impact.

The Art of the Visible Repair

The key, however, isn’s to simply abandon craft. The 'repair' in Kintsugi, the deliberate application of gold, isn’t haphazard. It requires skill, patience, and a deep understanding of the material. Similarly, writers need to hone their technical skills—mastering grammar, structure, and language—before they can truly embrace vulnerability.

The “golden lacquer” in writing isn't a lack of effort; it's a *conscious* application of craft to vulnerable content. It's choosing the right words to convey the nuances of emotion. It’s structuring the narrative in a way that maximizes impact. It’s editing with a critical eye, not to erase imperfections, but to refine and enhance the raw material.

Collecting and Preservation – More Than Meets the Eye

This principle extends to collecting, too. A fully restored antique accordion, while functionally perfect, often loses some of its intrinsic charm. The visible wear and tear, the faded bellows, the chipped keys – these are the things that tell a story, that connect us to the past. The true value often lies not in the flawless appearance, but in the tangible record of a life lived.

Similarly, a collection of handwritten letters, with their smudged ink and dog-eared pages, is far more evocative than a pristine digital archive. The imperfections are a testament to the intimacy and immediacy of the communication.

Finding Harmony

Ultimately, the art of Kintsugi, both in pottery and in storytelling, isn’t about denying the existence of flaws. It’s about transforming them into something beautiful, something meaningful, something undeniably more valuable than a flawless imitation. It’s about finding harmony between the technical polish and the raw, authentic emotion that breathes life into a narrative, that resonates with the reader on a profound, human level. Embrace the cracks, the imperfections – they are the golden threads that weave the tapestry of our stories.