Reimagining the Ruin: Finding New Genres from Familiar Forms

There's a certain melancholy beauty in the discarded. A poignancy that clings to objects worn smooth by time, fractured by accident, and deemed irreparable. We often see brokenness as an ending, a signal to mourn what’s lost. But what if that’s not the whole story? What if the cracks, the fissures, the fractures… what if those are where the true artistry begins?

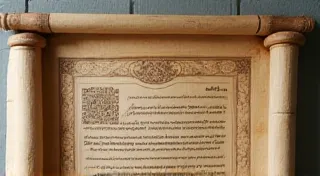

This philosophy lies at the heart of Kintsugi, the ancient Japanese art of pottery repair. It's more than just gluing a broken bowl back together. It's celebrating the breakage, highlighting it with lacquer dusted with gold, silver, or platinum. The repair becomes an integral part of the object's history, a visible testament to its resilience. Each golden seam whispers a story of damage, healing, and ultimately, a newfound beauty.

The Echo of Accordions: A Personal Resonance

My own fascination with reimagining the ruin stems, in part, from a deep affection for antique accordions. My grandfather, a quiet man of immense skill, played a Hohner Monarch. It was a magnificent instrument, its bellows worn supple with years of use, its keys ivory-yellowed with age. Over time, it developed its own collection of imperfections – a cracked reed, a sticky key, a tear in the bellows. He never sought to ‘fix’ it perfectly; he played it with its quirks, its personality woven into the melodies he coaxed from it.

Then, one day, it was silent. A catastrophic bellows tear rendered it unplayable. My grandfather, nearing his own end, simply shrugged. “Everything breaks,” he’s said, his voice raspy. “The trick is to find the music in the silence.” He wasn't dismissing the loss; he was pointing towards a different kind of beauty. I remember staring at the damaged accordion, the sadness palpable. It felt like a small piece of my family’s history was lost. I briefly considered restoration, a full, meticulous repair. But something held me back.

Instead, I started researching the history of the instrument. I discovered the meticulous craftsmanship involved in its construction – the painstaking hand-bumping of the reeds, the careful shaping of the wood, the artistry of the leather bellows. I began to see the accordion not just as a broken object, but as a tangible connection to a lost craft, a testament to human ingenuity and perseverance. The imperfections were no longer blemishes; they were markers of authenticity, echoes of the hands that had played it and the music it had produced.

The Craft of Kintsugi: More Than Meets the Eye

The philosophy behind Kintsugi is deeply intertwined with the Japanese worldview, particularly concepts like wabi-sabi – the acceptance of transience and imperfection – and mushin – a mind free of preconceptions.

The process itself is surprisingly complex. Modern Kintsugi often utilizes epoxy resin mixed with gold powder for strength and easier application, although traditional methods involve a lacquer called *urushi*, which requires years of training to master. The broken pieces must be carefully cleaned, reassembled, and then coated with the precious metal. The entire process can take weeks, even months, depending on the complexity of the damage. It's a labor of love, a meditation on the cyclical nature of existence.

The beauty of Kintsugi lies not just in the finished product, but in the journey. It’s a visual reminder that things fall apart. That’s a universal truth. But it’s also a reminder that what emerges from that fragmentation can be even more beautiful, more valuable, and more meaningful than what existed before.

Genre-Bending and the Art of Storytelling

The principles behind Kintsugi resonate deeply with the creative process, particularly in writing. As writers, we often strive for perfection, for seamless narratives, for predictable structures. But sometimes, the most compelling stories emerge from the cracks, from the unexpected detours, from the genre-bending experiments that defy convention.

Think about a historical fiction novel that incorporates elements of magical realism. Or a science fiction story that explores deeply personal themes of grief and loss. Or a romance that subverts traditional tropes and challenges societal expectations. These are stories born from the collision of disparate genres, from the willingness to embrace the unexpected, from the courage to experiment with form and structure.

Just as Kintsugi transforms broken pottery, this act of creative re-imagining can transform tired tropes and cliché narratives into something fresh, compelling, and deeply resonant.

Collecting, Restoration, and the Value of Imperfection

For those drawn to antique instruments like accordions, or fragments of pottery, there’s a growing appreciation for what’s often called “patina.” This refers to the marks of age – the wear and tear, the discoloration, the subtle imperfections that speak to a history of use and care. While complete restoration can certainly return an object to a pristine condition, it can also erase the very character that makes it unique.

Similarly, in collecting Kintsugi pottery, the value isn’t solely determined by the quality of the gold repair; it’s inextricably linked to the beauty of the breakage itself, to the story that’s etched into every golden seam. It’s about recognizing the inherent worth of imperfection, the beauty of resilience, and the power of transformation.

My grandfather’s accordion remains silent, a poignant reminder of a life lived fully, with all its joys and sorrows. It’s a fragmented echo of the music he created, a testament to the enduring power of the human spirit. And in its brokenness, I see not an ending, but a new beginning – a new genre, a new story waiting to be told.