The Dust of Ages: Finding Truth in Wabi-Sabi and Writing

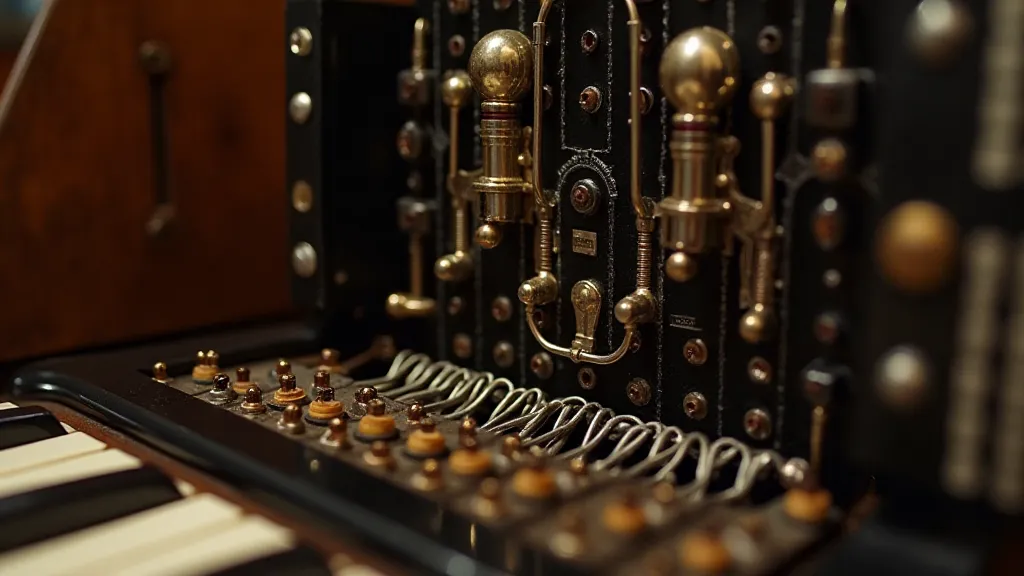

There’s a particular scent that clings to old things – a fragrance of paper and time, of leather and fading ink. For me, it’s most potent in the presence of antique accordions. My grandfather collected them, a quiet, stooped man who played with a melancholy grace that seemed to draw the music directly from his soul. These weren’t pristine instruments, mind you. Many bore the marks of a life well-lived – scratches on the bellows, keys that stuck, a general air of having been loved and used, then left to gather dust in a forgotten corner. Seeing them now, decades after his passing, evokes a profound sense of loss, certainly, but also a deeper understanding of the Japanese philosophy of wabi-sabi.

Wabi-sabi isn't easily translated. It’s more a feeling than a definition. At its core, it’s an acceptance, even a celebration, of imperfection, impermanence, and simplicity. It's about finding beauty in the cracks, the wear, the things that others might deem flaws. It’s the antithesis of the relentless pursuit of perfection that dominates so much of modern life. It's acknowledging that everything is in a constant state of flux, and that true beauty resides in embracing that inevitable change.

The Echo of Kintsugi: Repairing Not Just Pottery, But Perspective

The practice of Kintsugi beautifully embodies wabi-sabi. Literally translating to “golden joinery,” Kintsugi is the traditional Japanese art of repairing broken pottery with lacquer dusted or mixed with powdered gold, silver, or platinum. Instead of disguising the damage, the breaks are highlighted, becoming an integral part of the object’s history and beauty. The mended pot isn’t diminished by its cracks; it's enriched, its story deepened.

I remember watching my grandfather painstakingly repair a chipped teacup – a delicate porcelain piece passed down through generations. He didn't attempt to erase the damage; he celebrated it. The golden lines weren't just patching the cracks; they were narrating the cup’s journey, a testament to its resilience. It was a powerful visual metaphor for life itself – we all experience breakage, loss, and pain. Kintsugi reminds us that these experiences don't define us; they refine us, adding layers of complexity and beauty to our being.

The historical context of Kintsugi is fascinating. While the exact origins are debated, it’s often attributed to a 15th-century shogun, Ashikaga Yoshimasa, who, disappointed with the repairs made to a favorite Chinese teacup, demanded a more aesthetically pleasing method. This led to the development of Kintsugi as we know it today – a process that transforms a broken object into a unique and valuable work of art. It’s a perfect example of turning adversity into opportunity, of finding grace in unexpected places.

Craftsmanship and Collecting: Appreciating the Hand of Time

There’s a profound connection between appreciating wabi-sabi and appreciating craftsmanship. The imperfections in an antique accordion – the slightly uneven stitching, the subtly warped keys – aren’t flaws; they’re evidence of the human hand that created it. They tell a story of skill, dedication, and the inherent limitations of the artisan. Modern manufacturing strives for flawless uniformity, but the beauty of a handmade object lies in its unique character, its subtle irregularities.

Collecting antique accordions, or any antique for that matter, isn't about acquiring pristine objects; it’s about acquiring history. It's about connecting with the past, about holding a piece of someone else’s story in your hands. Each scratch, each dent, each faded inscription, contributes to the object's narrative. It’s a tangible link to a time gone by, a reminder of the lives lived and the stories untold.

Consider the careful selection of materials in older accordions – the richness of the wood, the quality of the bellows leather, the precision of the reeds. These were crafted to last, intended to be passed down through generations. Today, we often replace things as soon as they show the slightest sign of wear, but the older instruments stand as a testament to a different mindset – one that values durability, longevity, and the inherent beauty of well-made things.

Finding Your Voice: Writing with the Dust of Ages

The principles of wabi-sabi extend far beyond pottery repair and antique collecting; they profoundly influence creative endeavors, particularly writing. We often strive for perfection in our writing – polished prose, flawless grammar, perfectly structured narratives. But sometimes, the pursuit of perfection can stifle our voice, preventing us from expressing our true selves.

Embracing wabi-sabi in writing means allowing for imperfections – raw emotions, unexpected tangents, even grammatical errors. It means writing with honesty and vulnerability, allowing your unique voice to shine through, even if it’s a little rough around the edges. It’s about accepting that your writing, like life itself, is a work in progress, constantly evolving and changing.

Consider the beauty of a handwritten letter – the slightly uneven ink, the occasional blot, the personal character of the script. These imperfections aren't flaws; they add warmth and intimacy to the message. Similarly, in writing, allowing for moments of imperfection can create a more authentic and engaging experience for the reader.

My grandfather’s accordion playing wasn't technically perfect. Sometimes, a note would be flat, or a rhythm would be slightly off. But it was the imperfections that made it so beautiful – the raw emotion, the heartfelt sincerity. And that’s the lesson I carry with me, both in my appreciation for antique instruments and in my approach to writing – to embrace the dust of ages, to find truth in imperfection, and to let my voice resonate with the beauty of a life lived fully and authentically.